from Lilith: Independent, Jewish, and Frankly Feminist

Click here to view all Lilith articles by Merissa Nathan Gerson.

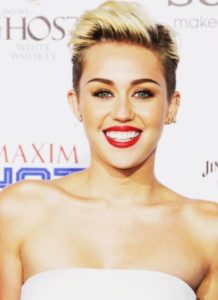

Miley Cyrus and a Whole Lot of Wrong

August 27, 2013 by Merissa Nathan Gerson

I have what I am going to term Miley fever. It started when I began watching the VMA replays and there she was, in her horrible glory, an emblem of America’s worst social ills. Then, what followed, an obsessive reading and re-reading of the articles meant to illuminate what we had just witnessed. And one by one I realized the writers were themselves exhibiting subtle sexism and racism of their own. Is Miley the social ill, or is she the catalyst to revealing our deepest issues?

I have what I am going to term Miley fever. It started when I began watching the VMA replays and there she was, in her horrible glory, an emblem of America’s worst social ills. Then, what followed, an obsessive reading and re-reading of the articles meant to illuminate what we had just witnessed. And one by one I realized the writers were themselves exhibiting subtle sexism and racism of their own. Is Miley the social ill, or is she the catalyst to revealing our deepest issues?

It wasn’t just the sideways tongue, or the bad costumes, or the wannabe Katy Perry set. It wasn’t the poor allusions to Britney, or the fact that there was little to no actual dancing happening on that stage. It was the basic fact that first and foremost, not even naked and alone, not even on the most intimate of beds would anyone want to see or experience those lewd moves. They weren’t sexy, they weren’t strip club worthy, they weren’t elegant, they weren’t really anything. There was a kid on stage with a lot of stuffed animals dressed as black women, or black women dressed as stuffed animals, and she was acting out everything she learned and didn’t learn on TV.

And someone, someone somewhere sanctioned the absurdity. Miley doesn’t act alone. Billy Ray Cyrus and Miley Cyrus together still need to be approved. Someone picked out that set, those bad costumes, and choreographed that show. That is what gets me. A collective of people agreed to performing, to allowing a black woman in a thong over her animal print leggings to bend over as Miley went to town on her behind. And then the backup dancers, the teddy bear black people. High brow writers called it a “Minstrel Show” but I want people who didn’t go to college for race studies, for white people who don’t get the whole shebang, to understand how on a basic level this show was a spiraling of crap choreography, absurdly vulgar and unsexy un-dancey gestures, and a whole load of treating black women like animal object props for a skinny white girl’s teenaged acting out.

What happens when a white girl doesn’t know herself and can’t find her own identity post pop-stardom? She looks to the black people for dance moves and gestures and appropriates them in a sloppy way. She attempts to “become something” by pretending to be “them.” Why was this so extra awful? Because not only was she stealing from what she might reductively deem “black culture” with her bad dancing, but she simultaneously demeans and fetishizes the black female body on her stage. That is a whole lot of wrong.

And why does this matter to me as a Jewish feminist writer? Because as a Jewish woman it is my job to advocate that women not be objectified or demeaned, and yes, that always includes black women. It means that I don’t want young white girls dancing in a way that alludes to, well, nothing, not even sex, not even sexiness, but the odd degradation of self and music industry standards on a series of poor dance moves and lewd gestures. It has nothing to do with “sluttiness,” but some modern understanding of tznius, defined by sexual dancing that is classy or choreographically informed where Madonna and Beyonce are the limit.

And being a Jewish feminist woman includes not wanting the racialization and animalization and fetishization of bodies on national television. It means holding a steady day-to-day awareness of my own privilege as a white Jew, and also keeping an eye on the white girls gone awry, or the black women toted along with this skinny white lady’s antics. It means Miley fever needs to be broken with some serious questions. Do we hate Miley? Do we look at her as awful, as an isolated ill? Or are we all to blame for the culture that shapes and promotes and funds and obsesses over an ignorant white girl smearing racist vulgur trash across a stage meant for a national audience? The only way to break the fever is to begin to pay attention.

- See more at: http://lilith.org/blog/2013/08/miley-cyrus-and-a-whole-lot-of-wrong/#sthash.jecswDFY.dpuf

German and Soldier, Falling in Love

December 6, 2012 by Merissa Nathan Gerson

It was two AM on a Sunday evening, and I found myself with a German woman and a male former U.S. soldier on a Tel Aviv beach. My life has a way of scooping me up and placing me in places, beautiful places, with beautiful but complex people. It was no simple après-midnight gathering. It was a post-bar, post-language-class indulgence in English.

We were in Israeli Ulpan and we were to speak Hebrew, rak iyvrit. But there were not enough Hebrew words to navigate sensitively the space holding three worlds: one German, one Jewish, one American military all in the state of Israel. We wanted, I wanted, not they to talk about the Holocaust.

I don’t know exactly how or why it happened but we had been honest all night and it was just the three of us and they, the German and the solider, were falling in love, and so by osmosis I was falling in love and I needed, desperately, to unveil my little heart.

That unveiling involved shedding a layer and revealing a giant hole left by a trip to Poland. Beneath a blanket of stars on three folding beach chairs I used their ears and my mouth and I poured a tall glass of Holocaust memory. I told them about my father. I told them about the Siberian labor camps and the displaced person’s camp and I told them about Poland, post-war. I told them about my Jewish family having no place in this world until they arrived illegally in America in 1950 with false names. I told them about my father’s favorite party-wear, his DP camp rations card, and I told them about the graves in Poland, about Belzec and the incomprehensibility of everything I was saying. I told them how I was only beginning to understand, only beginning to let the pain in, just in time to let it out.

The soldier was silent for a very long time, and then the German girl spoke and she cried a little and said she knows, she knows it is unknowable. I realized listening to her that she understood what I understood which was that it was all too much to digest with this mind, this heart, this English language. We needed Hebrew and German, military speech, civilian speech and the words of politics, of religion, and beyond to even start to piece things together. We were learning Hebrew to decode the matrix of horror and its delicate entrance into what had become our supremely non-horrific lives.

The German woman was, for a split second, a salve to my open wound.

After she cried on that beach and after I realized I was not alone in carrying this giant war between shoulder blades, the soldier felt the need to speak. He spoke in a voice unlike our voices, in a tone completely separate. He spoke in objective terminology. He spoke not of his life or his heart, but of “the Jews” and “the situation” in Europe. Everything he said was concrete, as if we had spoken without borders and he was suddenly using words to draw sharp lines, to delineate the black and to delineate the white.

His personal anecdote was not of the war he had seen, the battlefields he had waded through, nor of the people he knew who had been victims of war; he spoke of the movies. He talked about how “Schindler’s List” made him cry, and he talked about how laughter is medicine. He had told me stories one night at a bar about what he had seen in his life, he told me about this medicine, the medicine of laughing in the face of destruction, he told me about the Israeli soldiers he had met and about how they laughed at the Holocaust. He told me this once and it resonated. He said it again another night, twice. The first time it was touching, the second time reductive.

And now, sitting on the beach beneath a clear night sky, he felt the need to say it a third time. He did not say “joy” is imperative, he said, “You have to laugh at the situation.” He told me what to do. He told me how to cope. He talked at me as if I had not spoken, as if I were not Jewish, as if “the situation” were a containable something, a happenstance, a linear occurrence. He told me to laugh at the slaughter of my family, as if that could possibly help. He did not hear how fresh the wound was, how close to the arteries, how deeply embedded. He did not hear that laughing at it, not to move through it, but at it – this would be as if to laugh at the gravesite, with an open casket, as if mocking and torturing the spirit of the dead.

It was then that that openness began to close, not just close but invert, shrink, run, hide, subvert all surfaces and lay flat beneath the earth. Because he did not only speak of this foreign entity “the Jews” as if I had not just illuminated that “the Jews” were me, my family, their family, and their family’s family, but he also felt the need, over and over again, to ask how it was possible that the Jews “let this happen to them,” how some Jews “just took it.” Some Jews. My Jews. Me.

I walked away then. I had to leave. Whatever medicine was passed to me by the German girl was now obliterated. There were no words and she asked me to hand her her bag. I walked home like a zombie and lay in my bed and woke in the morning and ate breakfast and I had words in my head, on repeat: “The Jews just took it.” I crawled back into my bed. I closed the curtains and pulled the covers over me and I curled in a ball and I braced myself as my heart leaked as much as it could of the pain that soldier caused with his words. English words. Words that might have been more carefully plotted had they been in Hebrew, or German for that matter.

I knew the U.S. soldier had no intentions of hurting me or causing me pain. I later determined he was speaking at his capacity for emotional presence, that he thought he was “opening up” as he put it. I concluded that the soldier reverted to objective terminology because he had caused similar pain to the lives of others with guns and bombs in his own life. I assumed our space was a space he could not inhabit and so he drew borders, lines, walls, and those walls broke my heart.

Years later at an art history class an artist spoke of their work in Germany. One piece was a Berlin public installation, a glass hole in the sidewalk that peered down into a room. The room was empty, sparse, just lined in bookshelves without books. One girl in the audience raised her hand and asked, “What is the point of art like this? I was in Berlin and I saw the piece and I did not understand. What is the point if the audience does not understand?” And I thought to myself, that is the point of the piece, to force you into a blank room with missing pieces where you understand absolutely nothing, not why you are there, not why it is there, nothing. This is the beginning, to me, of facing the Holocaust. Without structure, without clean answers, just a broken heart and an empty room.

There are Rules

June 1, 2011 by Merissa Nathan Gerson

There are rules, somewhere, about how to be a Chasid on an airplane. In that same rulebook there are most likely also a set of behavioral norms for a woman in stretch pants lying about in the back of the plane.

My leg started swelling on a flight to Budapest. I went to the flight attendant for ice and took to the empty row in the far back of the plane where I could elevate my knee. Sitting across the aisle was a swipe of off white and black stripes. A giant man in his late thirties with gorgeous greying peyot was davening in the back of the plane. When I walked by in my thigh defining outfit there was a protective whisk of the tallis.

I decided things; like he hated that I could see him pray. He was wearing a special tallis with silver adornments along the hem at the top. He was wrapped in tfillin, his head covered by his shawl. I was a bit jealous; I wanted to pray and get dressed up in costume to do it. And in addition, I felt evil. If he had seen me, and in my female secular glory no less, was I not the interruption to his prayer and piety?

I sat across and faced the window so I wouldn’t flash my naked knee as I iced it. I had my back to my Chassid friend and suddenly felt something on my neck. He was standing now, and whipping his tallis about, mostly striking my face and neck with the fringes. I thought it was a joke. Then I thought he had special ownership issues. Then I was angry, convinced he was purposefully tracing a tallis across my head to somehow purify me.

I don’t like being in confined public spaces with orthodox Jewish men because I don’t understand the boundary. I don’t know when I need to stop and protect their piety, or when I need to stand as I am. On the sherut to the airport a young yeshiva bucher got on last. All the seats were taken and he had to make his way to the back and squeeze between two women. All I could think was how this was assur, and how he would have to go to the mikvah to purify himself.

On the plane I whispered assur under my breath at one point, an ugly effort to shame my Jewish neighbor. I spent most of the flight, especially after taking measures to turn away from the praying man, frustrated and annoyed with being shunned and being touched by his tallis, his belly, etc., as he moved about freely. I resented his sense of entitlement. I resented, most of all, how mid prayer, tfillin at the forehead, he stared down the bodies of women walking past him en route to the bathroom.

Was I to give him a break, a man not used to people dressed with such attention to curvature? Or was he a misbehaved representative of a people, donned in external religious garb and defying the expectation that while praying, he not look at women with lust? A wise woman tells me, over and over, that 90% of what you feel is related to your own life in the past, and the issues therein, and 10% is related to reality as it happens in real time.

This man was a catalyst, a trigger for a year living in Israel unsure whether I was obligated to follow the laws laid out in front of me, or whether finding my own balance was permissible. When giving into the matrix of religion, secular values of gender roles don’t translate well. I don’t do mehitzas, and I only cover myself for the respect of the communities I enter. One guy told me early in the year that women’s clothing choices reveal how much self-respect they have. In other words, my low cut tank top and leggings were markers of some deep self-hatred.

I internalized the voices around me, the woman who told me she loves to sing but won’t do it walking home in fear of kol isha. I heard the honks I got on Shabbos; I knew what it meant when I didn’t count for a minyan. I learned, over and over again about the value of concealing beauty, of how the matriarchs nearly burned their people down with the sheer power of their looks. We are asked to go under arrest not because we are unworthy, not because we should be hidden, but because we are so exquisite that something might happen if too many men bear witness.

I can argue two sides, three, even five sides to every religious argument. But what this leaves me with is a lack of ownership and a myriad of contradicting emotions when faced with a large man outwardly declaring his relationship with G-d in a way that directly infringes upon my personal space. The Chassid on the plane forgot his siddur when he got off. I had ducked a minute or two before, a bit peeved as he repeatedly reached directly above me for access to his suitcase.

I had flashbacks to the whipping tallis, and was worried he would whack me in the head with his small black bag. He saw me shudder and duck and he unexpectedly looked down, directly into my eyes, and said, “I watch, don’t worry, I watch,” with a twinkle and a grin. He was suddenly a big puffy teddy bear with a heart of gold. Memory erasure is also a problem when in the company of G-d fearing, soul sparkling people. If the present moment is exquisite, then why bother resenting being shunned a few minutes prior?

He walked off at that point, tzitzis revealing a paunch, and turned when I called him. “Slicha!” I yelled. I tapped the Israeli man in front of me and asked him to yell in my place, a silent understanding between us that a man, not a woman, needed to address this guy. “Hey,” he said. And at the English my giant friend turned. “You forgot this,” I told him sheepishly, handing him the prayer book while making sure not to touch him. And again, he beamed, so wide, “Thank you, that is very kind.” And in my imagination, as much as I can find the ogre in a man who won’t let me crawl under his tallis and daven in the back of the plane alongside him, a man who uses religious law to corner me, I also conjured up a blessing, convinced that in praying and walling me out, he was asking G-d for the healing of my swollen leg.

Tags: Merissa Nathan Gerson

- See more at: http://lilith.org/blog/2011/06/there-are-rules/#sthash.pZRaTxUd.dpuf